|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

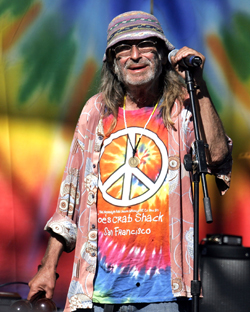

Color images from the

Summer of Love 40th Anniversary Reunion

September 2007 Golden Gate Park

San Francisco

|

|

|

"The present revolt of youth, the new radicalism, the democratization of the avant-garde, are all aspects of a worldwide revolution in the very foundations of culture, basic changes in ways of living, the emergence of a fundamentally new civilization."

--Kenneth Rexroth, "The Alternative Society: Essays from the Other World," 1967-69

"Truth and individual freedom. Freedom of expression. Creativity, love and respect for things. Freedom for an individual to make a choice-sexually, spiritually, and socially. The right to be different and still belong. Honor in refusing to fight without judging those who did. Our right to make a difference. Our right to think independently. Our willingness to share with others."

--Message of the Summer of Love 40th Anniversary website, advertising its free concert in San Francisco's Golden Gate Park Sept. 2, 2007

In 1967 poet Kenneth Rexroth gave his hopeful observation that the nascent emergence of a youthful Counterculture would become a worldwide revolution. Rexroth fashioned in his writings a Declaration of Independence for the artists and hippies that in his view comprised the gathering forces of momentous change. Forty years later Summer of Love Anniversary organizer Artie Kornfeld recalled the revolution's cultural Bill of Rights as he promoted a reunion for the Counterculture's surviving veterans. Upwards of 30,000 gathered in Golden Gate Park in 2007 to commemorate the legendary summer that now represents a high water mark in the generational rebellion of the Sixties. Many summers had passed and those present at the first "gathering of the tribes" were now conspicuous in their tie-dyed clothing and gray ponytails. It was a largely young crowd that gathered to recall experiences they never knew, to marvel at aging hippies, to attempt gingerly the approximate reconstruction of an unrepeatable moment. The cycle, the circle that "goes somewhere," had arrived for a warm September afternoon in Golden Gate Park. And while it appeared to be the original site of a Counterculture uprising, its place in contemporary space and time was now located at an entirely different intersection.

In Rexroth's view, San Francisco in the 1960s was the natural locus for a Summer of Love and the expression of what he called "the mass disaffiliation of postwar youth from a commercial, predatory, and murderous society . . ." Rexroth traced the city's tolerant and rebellious ambiance to its trade union roots in the 1930s. During World War II work camps for conscientious objectors were established throughout the mountains and forests of California. "These boys came down to San Francisco on their leaves," wrote Rexroth. "They met the San Francisco writers and artists who had been active in the Red Thirties but who had become, not professional anti-Bolsheviks, but anarchists and pacifists." At war's end a group of San Francisco writers and artists formed the Anarchist Circle and helped to develop a wide range of alternative activities and institutions, including a publicly owned radio station, experimental theaters, numerous magazines and periodicals, and a political consciousness well to the left of America's prevailing conservative mood. It was a "sympathetic environment" that Rexroth says the "so-called Beat writers" discovered during the early 50s.

Rexroth considered the Beat movement "only a minor episode" in the emergence of "a new post-modern, worldwide intellectual culture." While Beats espoused a sullen rebelliousness, they had "essentially the same values as did the world of the upwardly mobile new professions." The invasion of the Beats, according to Rexroth, "vanished like the Gauls from Rome. It was unable to hold the territory." And this was because its distinguishing characteristics represented a kind of vertical deviance not at all different from the dominant culture. "It hated sex. It used alcohol only for oblivion. One of the diagnostic signs of the Beat syndrome, very obvious to Kerouac's and Burrough's books, was contempt for women." Beats, Rexroth said, treated women "exactly as one would treat a casual homosexual pick-up in a public convenience." It was a "senseless nihilism" that contrasted starkly with "the rising tide of genuine revolt" represented by an emerging Counterculture "with a new ethic and a new kind of social responsibility and a new very male and very female sexuality-even though the squares are still bothered because everybody wears long hair."

Rexroth's essay goes on to praise the hippies in his midst as representing "a profound change in the patterns of life and an even greater change in its possibilities" and he notes that they are everywhere in the world, not just in Amsterdam, New York, on San Francisco's Haight Street or London's Notting Hill. It is a change with limitless potential and promise. "Today there is growing up throughout the world an entirely new pattern of life," pronounces Rexroth. "For several years I have called it a subculture of secession but this is no more-it is a competing civilization, 'a new society within the shell of the old' . . . in which there is an ever-increasing democratization of at least the possibilities for a creative response to life."

Looking back from the remnant realities of the early 21st century it is possible to embrace, as well as mourn, the poet's unrequited confidence in the Counterculture. Four decades have unwound Rexroth's hopeful vision into historical liturgies repeated and re-interpreted in more than 52,000 books and countless articles that, in the words of historian M.J. Heale, have "no agreed narrative." In constructing a historiography of the Sixties, Heale found that historians could not even agree on the length of the Sixties as an historical decade. Marwick's "long 60s," for instance, stretches from 1958 to 1974. Historian John Margolis says the Sixties began in 1964 while Bruce Schulman writes that the era ended abruptly in 1968. Suggesting that the decade has been seriously mislocated, David Frum argues that the Sixties did not really happen until the 1970s. Heale quotes Andrew Hunt who describes the Sixties as the "longest decade of the 20th century," underscoring the "fragmentation" in historical literature that reflects the diverse forces that shaped the era. "The personal, the pedagogic, and the political pull in different directions," writes Heale. As a period, the Sixties have become symbolic and "can be pushed into almost any shape to suit a particular agenda."

Several themes recur. As Heale points out the era has been portrayed as the intersection of boundless prosperity and an unusually youthful population. Another theme is that of political war in which class and economics give way to race and culture. The Sixties are sometimes recounted as the vortex of the Cold War and the struggle between liberal hubris and conservative anger. The decade can be seen as a time when "the personal became the political" or as the watershed separating industrialism from global post-industrialism. Over these and other scenarios, historians often drape the polemical templates of judgment, all of which in their elucidations of "what really happened" tamp down Rexroth's buoyant vision in a subsequent flood of historic consequence. Certainly the decade did not result in politically progressive change across the world. If anything, the Sixties may have provoked a more politically dominant conservative backlash. Authorities did not yield willingly to the Children's Crusade. War did not stop. Imperialism did not collapse. Poets did not destroy the borders between cultures and nations (global capitalists did). Yet much of what informs our daily lives today, the rise of feminism, multiculturalism, sexual freedom, spiritual diversity, deeply held personal entitlements to fulfillment and happiness, originate from the convictions and dreams of the Counterculture Sixties. Whatever the errors of his ebullience, Rexroth was right when he said "we can afford peace, we can afford creative leisure, we can afford to demonstrate and revolt until we get them . . . The best and most effective demonstration is simply to start living by the new values." So many millions did and whatever the competing paradigms of history, it can never be said that the Counterculture vanished liked the Gauls. But, as always, time and cycles loop all our intentions forward in ways that, despite our inspired certainty and anxious faith, cannot be foreseen.

The Tarot offers one way to interpret the cyclic discontinuities of our lives and their intersection with the vast, oscillating waves of other lives that, in their accountings, become the trends and themes of history. To this end the Sixties represent much more than the actors who, after all, comprised a small cadre of the larger baby boom generation. As Heale points out, just 13 percent of college students identified with the New Left in 1969. Off campus, only three percent of the same age group did. In the developing cast of characters of any historical epic we identify protagonists whose cycles of experience, whose struggles-in their efforts to address the discontinuity of living-stand out, but also stand alone. We don't have to be historically present to discover that we now stand with them. It is sometimes enough to be nearby. The Tarot offers a way to lift experience above the landscape of events and to touch the Counterculture's creative, disparate, and unbounded development without any need to draw together a thesis. We do, as sentient beings, seem continuously involved in "making sense" out of the seemingly senseless. But there are times when experience may itself be sufficient and there is no need to fully diagram the past or predict the future.

Within the Tarot's rich and ever augmented symbolism are paths to new perspectives, to places where poetry and history converge. Life may be an aberrant disruption of the cosmos. It may be discontinuous, disturbing, painful, and without apparent meaning. But it is a journey and its experiences-especially those at crucial and decisive intersections-rebound memorably as long as we live. Continuity, and its equipoise of surcease that silences all arguments, comes soon enough.

|