|

| Journeying the Sixties: A Counterculture Tarot |

|

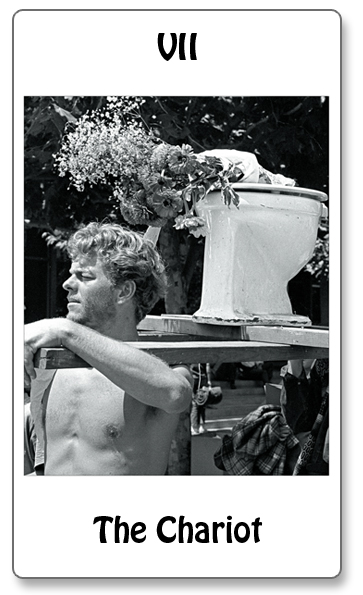

THE CHARIOT "We hold these truths to be self - evident, that all is equal, that the creation endows us with certain inalienable rights, that among these are: The freedom of the body, the pursuit of joy and the expansion of consciousness." --Statement from the Love Rally to Protest the New Prohibition of LSD. San Francisco 1966 The Chariot's Prince drives forward bearing into battle the mood of conquest on the back of inertia. The Chariot is like a big ship. Once it moves it is - for a period - irresistible. Once it stops, it is hard to move again. The momentum of the Counterculture rocked forward like the Chariot, amassed in the gatherings of thousands that seemed to characterize so many public events and celebrations. Concerts, be-ins, festivals, parades became the gathering points for the exercise of a hippie's inalienable rights: to enjoy freedom of the body (remove clothing), expand consciousness (consume mind-altering substances), and pursue joy (dance). The abbreviation of these rights to "sex, drugs, and rock 'n' roll" became a facile but effective rallying cry in the Counterculture's rapid evolution into a world phenomenon. But, like the Chariot, it was a phenomenon burdened with inertia; that would start, and then stop, and then seem to start again. San Francisco's 1967 "Summer of Love" in the Haight-Ashbury neighborhood was followed in the fall by the "Death of Hippie" observance in which street people declared the hippie - and all its media-amplified associations (psychedelic fashions, dope, and music) - dead and gone. Of course, the "Death of Hippie" (which also observed the one-year anniversary of the legal prohibition of LSD) was no more the end of the Counterculture than the "Summer of Love" was its beginning. Nevertheless, these two contradicting events highlighted the inchoate, sometimes incoherent, qualities of the movement and its tendency to break down just as it appeared to be getting started. Despite its internal tensions, the Counterculture of the 1960s held sway like no other flourish of bohemian impulse ever had. While hippies could claim the Beats as their intellectual antecedents (and often did), the pervasive influence of their lifestyle was staggering. The unconventional dress, liberal sexuality, anti-authoritarian viewpoints and apparent voluntary poverty of the Counterculture may have seemed typical of previous bohemian movements. The difference now was this new bohemia's immediate and pervasive influence. Bohemians of the past, whether artists and writers living in Paris garrets in the 19th century or Beatniks writing poetry in Greenwich Village cafes, lived almost reclusively, associating with artists and writers little known beyond a small circle of intellectual colleagues. By comparison, the Counterculture was a mass movement, enacted by millions. Rock's intersection now with a critical mass of young adults already familiar with the music's rich rhythms helped to inflame interest in the Counterculture. Eventually the music itself became an expression of alternative themes more subtle and complex than simply sex and drugs. But in 1967 it was John Phillips lyric "If you're going to San Francisco be sure to wear a flower in your hair" that played like an anthem on radios across the country and generated the children's crusade known as "The Summer of Love." No one knows if the expected 100,000 pilgrims ever arrived in the Haight that year. But two years later nearly 500,000 amassed at Max Yasgur's farm in Woodstock, N.Y., to enjoy their "inalienable rights" courtesy of the Counterculture Chariot. |