|

| Journeying the Sixties: A Counterculture Tarot |

|

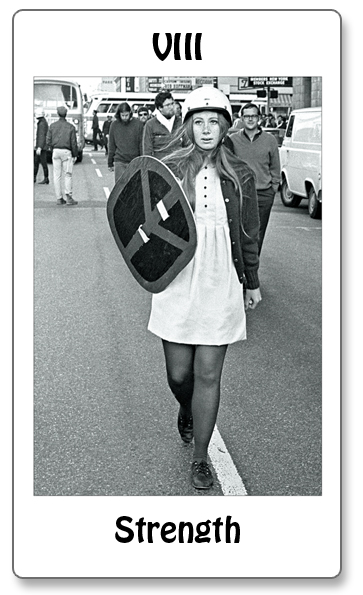

STRENGTH "We are people of this generation, bred in at least modest comfort, housed now in universities, looking uncomfortably to the world we inherit. When we were kids the United States was the wealthiest and strongest country in the world…many of us began maturing in complacency. As we grew, however, our comfort was penetrated by events too troubling to dismiss. First, the permeating and victimizing fact of human degradation, symbolized by the Southern struggle against racial bigotry, compelled most of us from silence to activism. Second, the enclosing fact of the Cold War, symbolized by the presence of the Bomb, brought awareness that we ourselves, and our friends, and million of abstract 'others' we know more directly because of our common peril, might die at any time." --Port Huron Statement, National Convention of Students for A Democratic Society, June 11-15, 1962 In the familiar Rider-Waite Tarot card Strength is a woman who holds open a lion's jaw. But the lion this woman must tame awaits her blocks away at the Oakland Induction Center for new army draftees. Compelled "from silence to activism," she bristles with her newly constructed womanhood, committed to non-violence but prepared for attack. It is a cool October day in 1967, during a nationwide student action labeled "Stop the Draft Week." She projects an outward strength, her body aligned in an expression of coordinated sexuality and personal power as she addresses bright, limitless horizons that don't seem very far away. She appears ingenuously invincible as she approaches the two thousand police officers armed with guns and clubs that await her arrival. The 59 college students who met in 1962 in Port Huron, Michigan, were already battle-seasoned veterans. Most, including Port Huron Statement author Tom Hayden, had enlisted in the emerging Civil Rights movement, joining sit-ins against segregation or bussing into the rural South on summer Freedom Rides to register black voters. Many had been arrested, beaten, or threatened with death by racist sheriffs or thuggish white supremacists. They were familiar with the risks that attended confrontations with authority, but also saw in their generation a wellspring of personal strength that could, in fact, should be committed to social and cultural change. Most colleges and universities discouraged student political activity, or specifically prohibited it. But inspired by radical sociologist C. Wright Mills (who urged his students to link personal troubles to public issues), the Port Huron activists articulated a set of what they called "Values." These included a call to develop individual political awareness "to bring people out of isolation and into the community . . ." and it meant challenging the university's authority to stifle on-campus political organization. "His belief that feelings of personal frustration and powerlessness ought to be connected to public issues was reiterated and developed by Hayden," historian James Miller writes of Mills' influence on the New Left, "becoming one basis for the characteristic assertion by the New Left (and later, by feminists) that 'the personal' is 'political.'" The political strength of the Counterculture was its anticipation of an unrealized dream. Perhaps it was motivated from a place of inexperience. It was hard to lose hope with so many "brothers and sisters" locked arm in arm. How could they fail to achieve something? Opposing them were the ideas that resonated in response: old coalitions, a Silent Majority, a new South, a critical mass much larger than all students combined that sat at home atomized and solitary. It was a mass without conviction, without any apparent strength. It spouted reactive opinions between bites of meatloaf and gulps of coffee. Yet on Election Day it was powerfully aligned with so much more strength than the New Left could ever hope to exert. Those in the movement knew that for every one of them there were ten of the other. Marxism, suddenly though fleetingly, seemed to make some sense. Activists could make a revolution; they could overthrow their fathers and mothers "for their own good" without any thought of how resistance might look. It was young strength; fresh and new but used as young strength has always been used: for the heavy lifting of others. At least its muscle was applied against war, rather than on its behalf; against racism rather than for it; for sexual freedom and gender equality rather than in defense of a 10,000-year-old patriarchy. Strength was used to seek a harmony of rhetoric and reality. "If we appear to seek the unattainable," the Port Huron statement concludes, "then let it be known that we do so to avoid the unimaginable." |