|

| Journeying the Sixties: A Counterculture Tarot |

|

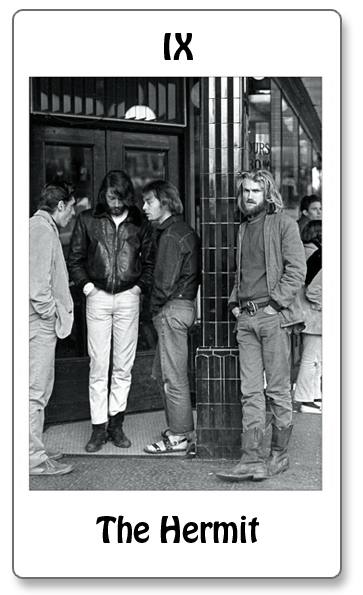

THE HERMIT "The youth of today are really looking for some answers—some proper answers the established church can't give them, their parents can't give them, material things can't give them. --John Lennon "The spiritual path is insult after insult." --Buddhist master Chogyam Trungpa Is the Hermit the seeker or the sought? He is pictured on the traditional Tarot card as a hooded ancient, walking with a staff and carrying a lamp. But does the lamp guide his way toward wisdom, or illuminate an inner truth? He is on a journey, as were the thousands of self-described hippies who crossed the nation in 1967, coming to San Francisco for the city's alleged Summer of Love. Perhaps 75,000 arrived for the summer, seeking to connect with the Haight-Ashbury's over-hyped zeitgeist of love and freedom. What too many found were what immigrants often find when they arrive in a country where the streets are reputedly paved with gold: disappointment, disillusion, and discomfort. Still, like immigrants, some stayed on after that summer of drug overdoses, vagrancy, and mean streets. They stayed through the fall and past the premature Death of Hippie funeral on October 6th. Their new lives were often hermetic, not hedonistic, as they begged for spare change, gathered at corners to share roaches or sell drugs, and rotated among "crash pads"(or scuttled into Golden Gate Park) to sleep. As with so many of the mass hippie migrations of the Sixties, the destination wasn't as important as the journey. In the collective arrival of hippie critical mass was an unspoken promise of love and peace. The promise could not be fulfilled but a little hope was enough to keep people moving, to sustain outbound expeditions that were really inward odysseys for a generation of adolescents now an army of hermits-in-training. Among the hippies all was shared, including poverty. It was like no other poverty in history, enforced by the young on themselves though they strolled through a civilization that produced wealth beyond any previous imagining. And they could still cherry-pick from the bloom of plenty around them, occasionally from their still-employed middle-class parents; or from a social system that offered food stamps and rent vouchers; even from the Mining Law of 1878 that allowed heartier hippies to squat free on mining claims in national forests, to live next door to Depression-era hobos who had arrived 30 years before and never left. The romance of having something for seemingly little or nothing held irresistible allure because it was a complete step removed from the contract of labor for capital. And this seemed ingeniously (and ingenuously) wise. Instead of joining the work force, hippies joined together to beat the rat race and innovate presumably cooperative solutions to the timeless human challenge of personal survival in a mass society. The goal was to make more time, though it frequently took more time to debate a solution and jury-rig it than it did to jump in the car and go to the store. Many oracles of the Counterculture were its most irascible curmudgeons. Allen Ginsberg's poetic lamentations against war and hypocrisy (along with his own drug-fueled inspiration) allowed him to cross the bridge from Beat to Hip and earn adulation among both. He thrust his homosexuality into the spotlight, if not oblivious to the opprobrium of the tenuous cabal of leaders referred to at that time as "the establishment," certainly not at all afraid. Bob Dylan, a seemingly anti-social folk singer with a weakness for alcohol, was found mumbling his prescient lyrics at the Bitter End on New York's Bleeker Street. Within a year he was popularly ensconced as the rock poet for a generation. Frequently the alienating contradiction within the alienated romance of anti-bourgeois revolution was that its most popular hermits grew wealthy beyond the reach of any boring member of the bourgeoisie. Rock performers, in many ways the mullahs of the movement, got rich quick. And what could be more bourgeois than that? |