|

| Journeying the Sixties: A Counterculture Tarot |

|

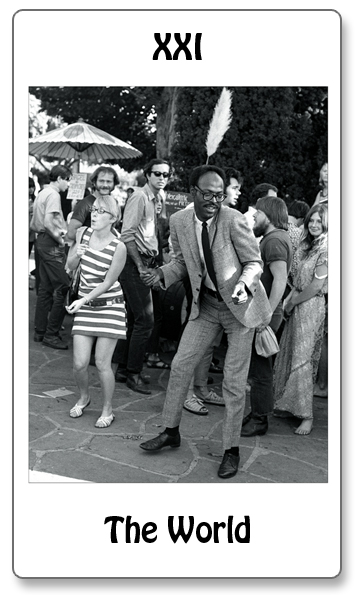

THE WORLD

"Step out onto the Planet.

--Lew Welch from "Hermit Poems" 1965 In The World the Tarot offers a moment's motion to represent eternity. A dancer rides the unheard rhythm beating beneath the image's placid surface. A principle of motion holds us in an eternal present that from the nearly imperceptible oscillation of atoms to the collision of lumbering galaxies pulls or pushes us along. In theory, motion makes the subatomic existence of our constituent reality only a probability. But the dancer reminds us there is nothing theoretical about experience. And for the Counterculture nothing was more important. The bodies of children on the verge of sexual adulthood are rich gardens for fragmentary and idiosyncratic experiences that amp up the first crucial encounters with mortality. Adolescence occurs at a vortex of risk and pleasure and, as culture critic Henry Giroux has written, "it has been through the body that youth displayed their own identities through oppositional subcultural styles, transgressive sexuality, and disruptive desires" that are central to "developing a sense of agency, self-definition, and well-placed refusals." A stream flowing toward the Counterculture contained a vigorous and somatic resistance to dominant moral rules and sexual taboos. A mass youth audience imbued with a musical resource of physical pleasure (and nonjudgmental about its source or impact) comprised millions of new and private sexual lives. Genitals form the core of the creative mystery, both its promise and terror. It is saddening, but not surprising, that human cultures try to suppress their bloom in the bodies of their children. The post-war generation may have been the first in history to escape puberty without significant sexual scarification. Long before the modern return of the Goddess, teenage women could explore the feelings and sensations of their own arousal, sustained by the frank themes of love, sex, and heartache that permeated a continuous personal soundtrack. When the birth control pill arrived in 1960, they were freer still to act (or not) on their desires without the risk of unwanted pregnancy. It was a nascent step in the sexual revolution that - at least at first - was much more a change in women's behavior than it was in men's. In the 1950s many teens had sex, but it wasn't considered a problem because much of it wasn't categorically "premarital." America had the highest teen marriage rate in the world. In the 1960s this changed dramatically as young women made conscious choices to postpone not just pregnancy, but marriage as well. Another flowing stream, that of possibilities well beyond the prevailing paradigm of work and family formation, joined those of rock music and sexual freedom. Men and women danced together but stood apart. The locus of the dance had moved from the male's "lead" to a centering point between them. Provocative gestures and routines still advertised a hunt for gratification but the core expression was from within and the gender-managed "choosing" of partners increasingly irrelevant. By Woodstock's momentous 1969 assembly, tens of thousands of young men and women swayed together in a teeming, anonymous and dancing mass. These Berkeley dancers represent well a celebration of divine motion that displaced all distractions; that found rhythms in the visceral unity of rock music; drama and elation in liberating encounters with sex and love; and lyrical perceptions in determined, sometimes dangerous, explorations of consciousness. What did anything matter but experience here and now? What did it matter to do anything but seek the alignment of one's inner sense of being with his or her outer activities, to synchronize oneself in a dance of life? What generation as a whole ever before had the freedom to think this way? The Whole Earth Catalogue first appeared in 1969, its trademark cover a photograph of our World caught against the black void of space. In his description of purpose, Stewart Brand wrote "We're as gods and we might as well get good at it." |