|

| Journeying the Sixties: A Counterculture Tarot |

|

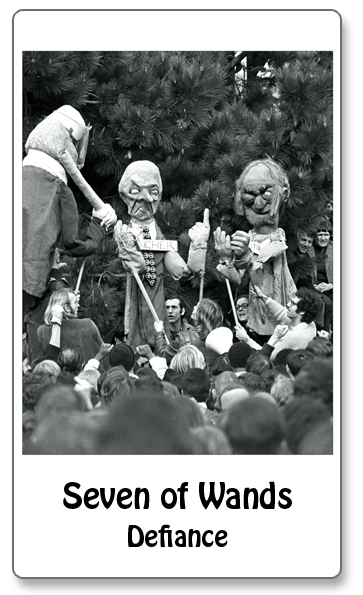

SEVEN OF WANDS "In Watts, Prague, Stockholm, Stanleyville, Gdansk, Turin, Port Talbot, Cleveland, Cordoba, Amsterdam, wherever the act and awareness of refusal generates passionate break-outs from the factories of collective illusion, the revolution of everyday life is under way." --Raoul Vaneigem, Situationist philosopher from "The Revolution of Everyday Life" 1967 "Personally, I always held my flower in a clinched fist." --1960s Yippie activist Abbie Hoffman Battle can be thrilling in a way that makes warriors feel momentarily invincible. The Seven of Wands is that charge of adrenalin that draws together the heart and mind and asserts courage with a quick, clever strike. Some have called the Seven of Wands the Purple Heart of the Tarot. Wand fire inspires an art of war. Only later when we reach the suit of Swords' harshly discriminating qualities does the relentless battle close in and threaten a fighter's spirits with its oppressive fatigue. Here, though, a flash of inspiration may be enough to hold the line. And as the Sixties progressed, inspired activists shaped out of the era's artistic innovations a remarkable arsenal of weapons. Giant puppets, street theater, die-ins, event-disrupting "zaps," were just some of the creative artillery to supplement protests against war, racism and injustice. Acknowledging their usually small numbers, many protestors knew that victory would come, not by vanquishing enemies, but by exposing them. The Civil Rights movement's reliance on non-violent confrontation had found early and enduring success by dramatizing the powerful moral distinction between peaceful victims and raging oppressors. Borrowing from the period's conceptual and performance art breakthroughs, artists converted wands of irony into figurative cudgels of disarming rhetoric. To win the battle in the streets was to win the argument against authority. To "act out" was to create on a stage of non-violent resistance a devastating theatrical assault on the social order's weakest premise. It was often an entertaining, memorable, and persuasive way to argue for, in Vaneigem's words, "the revolution of everyday life." Art's power to capture and politically engage people in their daily lives was recognized by the Diggers and other performers, but the basis for its application was articulated by the Situationists, European political and artistic activists who formed the Situationist International in 1957. The group's goal was to realize the radical political potential of surrealism as demonstrated in the Notre-Dame affair in 1950 when artist Michel Mourre, dressed as a monk, infiltrated an Easter mass and, standing at an altar, read a pamphlet proclaiming that God was dead. Strategic pranks could be revolutionary acts, provoking authorities into revealing missteps while jarring a surprised public into mnemonic awareness. An infantry of clowns and comics would soften targets by exposing their hypocrisy. Moreover, a small cadre could, with maximum - and non - violent - effect, execute brilliant political pranks. The radical Bread and Puppet Theater of New York began in 1965 to carry its 15-foot tall puppets in anti-war demonstrations. Puppets inspired Abbie Hoffman to lead a hippie "Flower Brigade" during a 1967 Veterans of Foreign Wars march in New York that supported the Vietnam War. Parading veterans attacked and beat members of Hoffman's small group, but the mayhem produced news coverage sympathetic to the protestors. At a press conference Hoffman declared that "the cry of Flower Power Echoes throughout the land. We shall not wilt." It was the beginning of Hoffman's career as a theatrical revolutionary that culminated in his partnership with Jerry Rubin and the founding of the Youth International Party (Yippies). The appearances of Hoffman and Rubin before the House Un-American Activities Committee and their subsequent trial as members of the Chicago Eight are now regarded as historic confrontations that left Congressmen, judges, and prosecutors sputtering. Hoffman, wearing a t-shirt made from an American flag that was torn from him by security guards, said proudly at his trial for flag desecration "I regret I have but one t-shirt to give for my country." |