|

| Journeying the Sixties: A Counterculture Tarot |

|

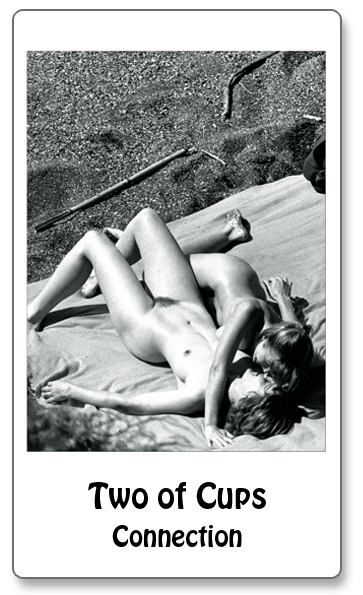

TWO OF CUPS

"Should I get married? Should I be good?

--Gregory Corso, "Marriage," 1958 Beat poet Gregory Corso's poem is an amused pondering on the road to marriage in which he separates a venerable social institution of connection and family formation from the experience of loving. He expresses a Beatnik's lack of confidence that he can love enough, and long enough, to stay in a marriage. But he is fearful, as he writes toward the end, "Because what if I'm 60 years old and not married, all alone in a furnished room with pee stains on my underwear, and everybody else is married! All the universe is married but me!" The Two of Cups is the card of connection. It is labeled "Love" in the Thoth deck, its two overflowing cups an appropriate symbol for the flush of emotions that generates relationship and proffers its hope of lasting binary happiness. It is as if the union of souls combines with bodily attraction to multiply the "power of two," - a power that, beneath lovers' touches, can create more than twice the pleasure or more than twice the despair. The Two of Cups advertises love as the integration of opposites that for so long was the requisite for marriage. The importance of opposites was maintained for centuries, embodied in polarized gender roles and their exclusive and required match to make a wedding. When gospel conservatives today say, "marriage must only be between one man and one woman" they embrace the gender unconscious that has haunted human culture with an imperative to make babies, and to guard that imperative with an exclusive, lifelong commitment enforced by the potent, aggressive male over the fertile, accommodating female. But the Counterculture had other ideas about love, acknowledging its strong attractions while challenging first the idea that opposites (as represented by the male/female polarity) always do attract and, second, that love's attraction belonged only to one partner. For the Counterculture, such gender extremes were unnatural. Cultural hypocrisy around marriage was so egregious (in 1967 sixteen states still prohibited interracial marriage) that it became imperative to explore new connections, some of them also extreme. Emboldened by its own sexually experimental adolescence, the Counterculture first acted on feelings of attraction as reason enough to have sex. Ideally, the goal was to live from a utopian sexual ideal of free and available love. As one might imagine life among a troupe of bonobos, sex could occur immediately with one lover, serially with many lovers, or simultaneously with a group of lovers. Acting on feelings of attraction was accepted as a natural response, as was a wider range of attractions that included gay, lesbian, and bisexual encounters. All that was required was mutual consent. Love was universal. Satisfactions were as possible, or impossible, as they perhaps ever were and the vast majority of hippies, students, and activists of the Sixties did not have gay, lesbian or group sex, or jump immediately into bed with the first attractive person. Couplings based on physical attraction could be as problematic as they were enjoyable. But by the mid-1960s new behaviors were possible and new choices inevitable. It would all start from scratch, beginning at the root of a primal desire that was draped in a blanket assertion of universal love. It was a primitive platform, but one from which to stage an embryonic and eventually thorough reassessment of human connection and the "power of two." |