|

| Journeying the Sixties: A Counterculture Tarot |

|

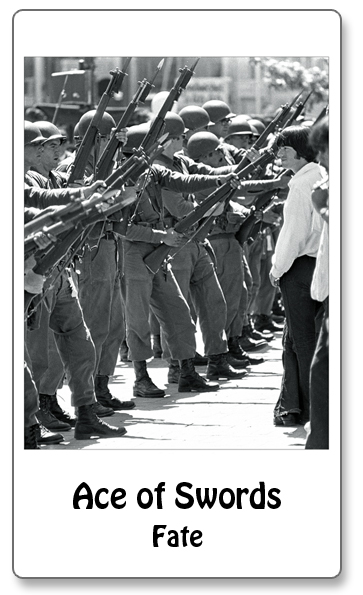

ACE OF SWORDS "One of the people close by said that Hurst was telling Lee, 'I'm not fooling around this time, I really mean business,' and that Lee told him, 'Put the gun down. I won't talk to you unless you put the gun down.' Hurst put the gun back under his coat and then Lee slid out on the other side . . . As he got out, Hurst ran around the front of the cab, took his gun out again, pointed it at Lee and shot him . . . Hurst was acquitted. He never spent a moment in jail. In fact, the sheriff had whisked him away very shortly after the crime was committed." --Civil rights activist Robert Moses recalling the murder of black farmer Herbert Lee by Mississippi State Representative E.H. Hurst, Sept. 25, 1961. Lee had angered Hurst by expressing an interest in registering to vote. The Ace of Swords is the triumph of an idea. During the Sixties ideas competed intractably and, as they hardened into beliefs, became swords that cut deeply into the fecund imaginations fed by the Cups. Where water fertilizes boundless dreams, the Swords return to a zero sum game. It is the slash of reality against the uplifting bloom, a "cutting down to size" of overgrown aspirations. As Robert Wang writes of the Ace in Tarot Psychology, "this is a power struggle; this is the card of ideological conflict, a battle over principle and over points of view where the strongest (and not necessarily the best) advocate is the victor." It is the truncheon and fire hose applied against Birmingham children marching for civil rights in 1963. It is the spray of police gunfire that murdered Black Panther Fred Hampton in his bed. It is the National Guard firing rifles at Kent State students in 1971 or Russian tanks rolling into Prague in 1968. Robert Moses was a native of the Harlem housing projects. He began working for the civil rights movement in 1960, becoming field secretary for the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). As director of SNCC's Mississippi Project, Moses traveled to the Deep South, attempting in 1961 to register blacks to vote in the rural counties of Amite and Pike. Out of 14,500 blacks eligible to vote, only 38 were registered in Pike and three in Amite. Amite especially was a stronghold of racism where a minority of white citizens had held power since the Compromise of 1876 ended Reconstruction. White citizens had driven blacks off their land; disenfranchised them, and . . . free of interference from the federal government . . . had terrorized them with lynchings and shootings. A few Amite blacks still owned land but only because their grandparents had fought back to keep it. Moses walked alone into this milieu and found a handful of Amite blacks willing to support a voter registration drive. One was farmer Herbert Lee. For a month after his arrival, Moses had contacted ministers, teachers, and farmers of the black community to try to organize a voter registration drive. As muckraking Sixties journalist Jack Newfield reported, civil rights workers had not even tried to enter Mississippi until 1952. The first was shot and killed and the second was shot and run out of the state. Next came Bob Moses in July 1961. He managed to register a handful of blacks before a state highway patrolman stopped him and put him in jail. Thereafter Moses was harassed, beaten and repeatedly arrested. When he showed up at the Amite county courthouse with a group of blacks who wanted to register, the clerk closed her office and more than 100 white men, all carrying guns, took over the building. Still, Moses managed to hold the interest of a few brave black citizens, and Lee was among them. Lee agreed to register just days after the courthouse incident, even though he'd heard that white farmer and state representative E.H. Hurst had threatened to kill him. Hurst made good on his threat, following Lee in his truck and forcing him out before shooting him once in the head with a .38 caliber revolver. Lee fell into the street in front of at least a dozen witnesses. Hurst escaped and by the afternoon had been acquitted by a coroner's jury that ruled Hurst killed Lee in self-defense. In so many ways the nation's Civil War of 1861-65 was fought again during the civil rights struggles of 1961-65. A little more than a year before Moses' arrival in Amite County, South African police had opened fire on non-violent black demonstrators in the town of Sharpeville, killing 69 people including eight women and 10 children. Had Lincoln lost the Civil War, had a Confederated States of America held sovereignty over the continental south, it is not hard to imagine that Martin Luther King's 1963 Birmingham march might have turned into a Sharpeville-like massacre. |