|

| Journeying the Sixties: A Counterculture Tarot |

|

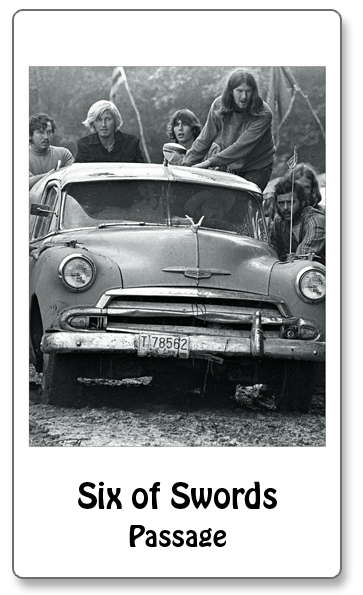

SIX OF SWORDS "I recall a Be - in in Fresno in Roeding Park one Sunday afternoon. I was sitting near a group of young farm boys, all crewcut, a few wearing cowboy shirts and levis, engraved boots, and all drinking beer. A young man with shoulder - length hair walked by. 'Hey lookadat. Isn't she cute? Hey, little girl, does your mama know you're out?' Lots of laughs. The young man went on his way, paying no attention, on his own trip. One of the cowboys called out after him: 'Hey, honey, how about gettin' in ya?' For the cowboys, long hair meant femininity and nothing else." - - Los Angeles Free Press writer Clay Geerdes from "Is Long Hair a Psycho - Sexual Threat to the State?" May 30, 1969 The journey is a metaphor for transition and the Six of Swords puts us on the road. But this isn't just a launch onto the highway. This is the discovery of a new direction, a destination not to be found on any map. Men in the Sixties took to the road to navigate a sea of deeply felt changes. As with the men here (wheeling an old car onto a communal farm in the Northwest in 1969) there was often a common bond, even if they did not speak to each other or look anywhere but ahead. Imbedded in the experience of a hip man's new humanity was a vexing confrontation with masculinity that seemed to dance between two poles of expression. One pole tended toward the rebellious and romantic outlaw, portrayed by the character Dean Moriarty in Jack Kerouac's On the Road or later by Peter Fonda as a hip motorcycle road tripper in the 1969 movie Easy Rider. These were what the Diggers referred to as "life - actors," men who carried their cultural wars into daily living, whose provocative dress and insurgent behavior advertised, sometimes threateningly or fatally, their flight from bourgeois domesticity. Toward the other end could be found qualities of the noble savage, manhood also rebellious and romantic but held within a spiritual balance connected with nature and rooted in mysticism. On one, long hair and brightly colored clothes were a kind of countercultural armor. On the other, they were the soft and touch - inviting appurtenances of love and peace. On both they were unmistakable declarations of something defiantly beautiful and, to the cowboys in Fresno, unmanly. Many Sixties men were somewhere between the poles of the truculent rebel and the contemplative peacemaker, seeking some middle way between action and reflection. But all pivoted on the profound changes occurring in the consciousness of women. A notion was brewing, one fed by Jungian psychology and amplified by popular Eastern concepts of yang and yin, that men could not be raised by mothers without incorporating the feminine any more than women could easily find their power without knowing an archetypal father. These Counterculture men of the Sixties were "new" men who had arrived at an historic moment. They were motivated to question authority, including socially authoritative versions of manhood and, even if they were not then (or ever) feminists, they engaged with the feminine as no other generation of men had ever done. By the early 1970s feminism's Second Wave was sweeping through Western nations. But no comparable men's movement has ever arisen. Instead, impulses of male assertion have brachiated widely, some liberating and some not. Groups have formed to help men recover from relationship - threatening anger and addiction. Pro - feminist men are represented by the National Organization for Men Against Sexism (NOMAS). Small in numbers, NOMAS urges men to address the ways hierarchical dominance controls men's behaviors and subjugates their earnest, loving qualities. Mythopoetic men's groups, sparked by the writings of poet Robert Bly, encourage men to explore their masculine natures in "men only" spaces where they can beat drums, sing, and express the presumably primordial qualities of an unfettered masculinity. Fathers' Rights groups support men in their roles as parents. But these groups are socially and politically bifurcated. One branch urges men to embrace positive parenting, to nourish communication with a child's mother, and to build a parenting partnership in which the emotional and reproductive labor of family formation is fairly shared. The other, embodied in religious movements like the evangelical Promise Keepers, authorizes men to assert their patriarchal leadership in the family, and to maintain household control through loyalty and discipline. Mothers more than males have effectively opposed the most physically invasive abuse of men: routine medical circumcisions of infant boys. And Gay Liberation is perhaps the most consequential men's movement, despite the fact that it seems to frighten heterosexual men the most. It was gay men who in the 1969 Stonewall riots in New York offered the boldest resistance to police abuse of civil rights. Since Stonewall, gay men have, with some success, worked to gain increasing social acceptance for their lifestyle while seeking reforms that include gay marriage and the acceptance of gay couples as adoptive parents. |