|

| Journeying the Sixties: A Counterculture Tarot |

|

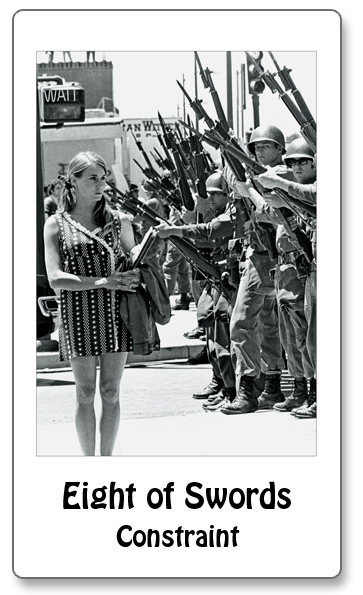

EIGHT OF SWORDS "When one group rules another, the relationship between the two is political. When such an arrangement is carried out over a long period of time it develops an ideology (feudalism, racism, etc.). All historical civilizations are patriarchies: their ideology is male supremacy." --Kate Millett, "Sexual Politics: A Manifesto for Revolution" 1970 "We call on all our sisters to unite with us in struggle. We call on all men to give up their male privileges and support women's liberation in the interest of our humanity and their own. In fighting for our liberation we will always take the side of women against their oppressors. We will not ask what is 'revolutionary' or 'reformist,' only what is good for women." --The Redstockings Manifesto, July 1969 Beginning with their activism in the Civil Rights and Anti-War movements, young, mostly college-educated women began in the mid-Sixties to address the apparent constraints of their own lives in an unprecedented surge of inquiry and action. As they wrestled with the dilemma of reconciling traditional social expectations about women with their own countering hopes and desires, it became apparent that the root of the problem lay in the political and cultural dominance of men. The smothering blanket over their new hopeful visions was the same one draped over those of their mothers and grandmothers, and all the mothers before them: a prevailing patriarchy that asserted male privilege over women's freedom. And what was most troubling about this revelation was that it went to the heart of most women's expectations about intimate partnership and love. For to sleep with a man, to love him, was in some sense to sleep with and love an enemy. This was apparent early on as young feminists sought the political support of their New Left "brothers" only to learn how deeply ingrained were men's fixed ideas of a woman's place, and how pervasive - in politics, in education, in science, in philosophy, in the arts, in religion, in family life, in sex - was the presumption that women played a secondary and supporting role to a man's power and achievement. So it became impossible for a feminist to address the emotional interplay of personal relationships without also addressing the personal politics of physical and economic survival. Within just a few years the developing women's movement produced a spreading feminine consciousness and an enormous body of literature that radically redefined the terms of social power and intimate engagement between men and women. It is not exaggerating to say that the Feminist Revolution spread like a prairie fire, not just across the United States but also around the world, and remains the widest and most enduring of the Counterculture's impacts. But the movement's first insurgent successes also met with a profound backlash. In her history of the modern women's movement, The World Split Open, Rosen ticks off the damage: the election of Richard Nixon in 1968 stiffened resistance to legal challenges to sex discrimination; in 1970 former vice-president Hubert Humphrey's personal physician sparked a national controversy when he stated that women were unfit for the presidency because they might be subject to "curious mental aberrations." In the same year the Catholic Church established the National Right to Life Committee to block liberalized abortion laws; preacher Billy Graham condemned feminism as "an echo of our overall philosophy of permissiveness," and in Arizona a group of women organized Happiness of Womanhood (HOW) that soon merged with the League of Housewives to support a woman's traditional role in the family. In 1971 Nixon vetoed the Comprehensive Child Development Act that would have provided childcare to all women, saying it would "lead to the Sovietization of American children." In 1972 Phyllis Schlafly attacked the recently proposed Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) and formed the organization Stop ERA that eventually led a successful fight to defeat it. Following the Supreme Court's 1972 decision to legalize abortion, a group called the National Committee for a Human Life Amendment began a well-funded effort to overturn it. Some 8,600 delegates at the 1973 Southern Baptist Convention passed a resolution asserting male superiority and the U.S. Senate, with no women members, unanimously passed an amendment to the Foreign Assistance Act that prohibited the use of funds for abortion services. By 1974 wealthy conservatives like Joseph Coors were financing anti-feminist organizations like the National Conservative Political Action Committee and supporting Schlafly's Eagle Forum. Schlafly accused feminists of hating men, marriage and children and said they were out to destroy morality and the family. "The race had begun," writes Rosen. "The antifeminist backlash had as much momentum as the women's movement." |