|

| Journeying the Sixties: A Counterculture Tarot |

|

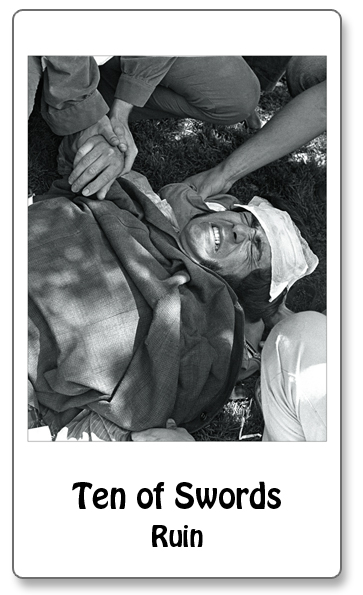

TEN OF SWORDS

Nixon: "See, the attack in the North that we have in mind . . . power plants, whatever's left . . . pol (petroleum), the docks . . . And I still think we ought to take the dikes out now. Will that drown people?"

--From the Nixon White House tapes, recorded on April 25, 1972 The Ten of Swords returns us to death, not the Death with a capital D of the major arcana, not the natural death that renews life. The Ten of Swords induces an arbitrary, delimiting doom. As the Ten of Cups is the card of abundant happiness, the Ten of Swords is the card of plethoric pain: the pain of sacrifice, the pain of annihilating retribution, the abrupt, disorienting pain just at the moment of immediate and sometimes surprising demise. It is a death that, according to Crowley, teaches the lesson that if one goes on fighting long enough, all ends in destruction. Conflict animated by the Swords builds irresistibly to the ruin of the Ten. Many confrontations between the Counterculture and authorities were predicated on resistance to emerging threats and long-standing injustices. They began in the 50s with protests against the proliferation of nuclear arms, and by the early Sixties grew to address the brutalizing consecutions of racism and the bloody, seemingly interminable wars of empire. A peace marcher writhes and grimaces after a police beating during a raucous 1968 demonstration in San Francisco. Assault came as a surprise; especially to white college students who had never experienced excessive police force and who found themselves suddenly on the ground in excruciating pain. It was a surprise, as well, when police departments went berserk (as they did in Chicago in 1968) and terrorized civilians, or National Guard troops panicked and fired their rifles into crowds of college students at Kent State and Jackson State in May 1970. It was always a surprise when white people were killed while exercising their rights. It was not such a surprise to black Americans who knew, as their parents and grandparents had known for so long, the cruel, desolating retributions of racism. Following the end of the Civil War in 1865, southern Democrats quickly regained political power in the South through a guerrilla war against Republicans who had taken control of Southern legislatures by registering former slaves to vote. Insurgent Southerners assassinated community leaders and newly enfranchised black citizens, forming organizations like the White Camellia and the Ku Klux Klan that, like the Viet Cong in Vietnam or the Sunni insurgents in Iraq, used terror effectively. By 1875 Mississippi Democrats retook the state legislature through a campaign of violence. In Yazoo County, for instance, there were 12,000 black residents but Republicans received only seven votes. Democrats in other southern states adopted Mississippi's terrorist tactics to take control of their own elections. White supremacists then rewrote their state constitutions to prohibit blacks from voting. Those who resisted were lynched by white mobs. Between 1868 and 1876 there were between 50-100 lynchings a year, continuing at a comparable rate well into the 20th century. In lynching photos that survive, we relive the arbitrary terror of the ultimate Swords sacrifice: in the incredulous stares of naked, scarred men about to be hanged or burned alive; in the prurient anticipation of the assembled mob; in those photos where corpses swing from poles or trees, the unmistakable evidence of an agonizing death. This was not the triumphal work of Kissinger's imperial butcher, a president who threatened to annihilate 200,000 Vietnamese with a nuclear bomb. Lynchings were carried out by everyday working class butchers who smiled for the cameras and sold their victims' body parts as souvenirs. Lynching photos of festive perpetrators surrounding the fresh corpses of their victims have a heartbreaking similarity to the scandalous GI snapshots of torture and prisoner abuse at Iraq's Abu Ghraib prison in 2004. At the funneling end of this history of racial violence, it took enormous courage in the Sixties to register black voters in the South, to hold strikes and sit-ins, to sit at the front of a bus or seek service at white-only lunch counters. As the decade began, lynching increased, and what would stop it? Lynching did not end until the Delta despots whose families had terrorized black American citizens for nearly a century were themselves attacked again by a Yankee army. Presidents Eisenhower and Kennedy both sent troops into Southern states to enforce civil rights laws and to protect black voters. It was the federal government's first significant military intervention in the South since Reconstruction, spurred by a new politics of non-violent resistance and, finally, by a growing national disgust with racist murders of innocent victims. It was a long time coming. |