|

| Journeying the Sixties: A Counterculture Tarot |

|

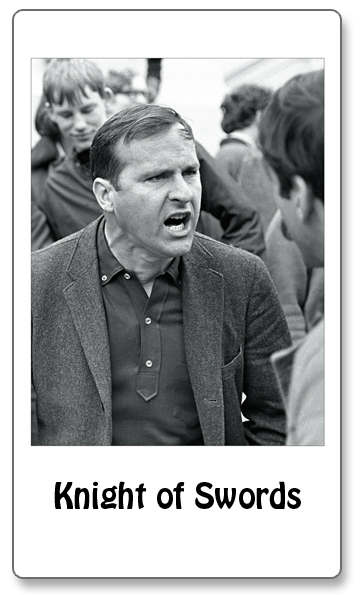

KNIGHT OF SWORDS "The Bible is without reservation in its condemnation of homosexuality . . . If a man also lie with mankind . . . they shall be put to death . . . This is certainly clear enough and there is not a single text in all of the New Testament to indicate that this penalty has been altered or removed . . . " --R.J. Rushdoony, "The Institutes of Biblical Law" 1973 A preacher rails near UC-Berkeley's Sather Gate, a Knight of Swords charging relentlessly into the secular ranks of passing students. He throws his aggressive righteousness against a liberal arts tradition of inquiry and experience. In 1967, students laughed at the indignant evangelist, goading him into debates he could never win. Like the airy Knight, he quarreled with blind courage and fanatical futility, confident that the Lord had sent him here, to a Godless university campus in the Sixties, to rescue souls for Jesus Christ. To students and faculty he appeared an amusing anachronism, a time traveler from the revival camps of the 19th century or from off a sidewalk outside the Tennessee courthouse where in 1925 John Scopes was convicted of teaching Darwin's theory of evolution. Surely as he screamed liturgy at an audience of uncommonly critical minds, the preacher appeared destined for history's renowned dustbin. Yet long after the demise of the Counterculture, long after the passing of SDS and the Weathermen and the Death of Hippie, the preacher is still shouting. And by the end of the 20th century he had joined a chorus of evangelical Christians with a determined agenda for social change, and political clout considerably stronger than any the New Left could have ever hoped to attain. America, a nation colonized by religious fanatics so extreme they were thrown out of 17th century Europe, has defied the Western humanist tradition with periodic religious revivals that challenge social tolerance and scientific thought. So-called "Awakenings" have occurred with surprising regularity since the 1730s and the current evangelical revival is considered the Fourth. If the Sixties Counterculture, as Theodore Roszak has proposed, was a new version of the Romantic Movement, then the rise of the Religious Right is another version of the nation's periodic revival of religious fundamentalism. But it is a version like no other. For one, it is coercively evangelistic; that is, it seeks to convert, or reconvert, everyone to fundamental Christian faith. For another, many evangelicals today wish to see their religious values incorporated into public policy. Formed in 1981, the Council for National Policy (CNP) has raised tens of millions of dollars in campaign funds to promote the Religious Right political agenda that includes amending the U.S. Constitution to declare America a "Christian nation." Finally, the modern American Religious Right touts a Calvinist intellectual foundation, an extensive media empire bankrolled by wealthy supporters, and decisive influence with one of the country's two major political parties. It is the most powerful of any of the nation's Awakenings, and one its supporters are determined will never fade. If the modern rise of the Religious Right has an intellectual father, it could well be Rousas John Rushdoony whose 1,894-page book The Institutes of Biblical Law proposes that Old Testament laws should apply to modern societies. Rushdoony himself graduated from UC-Berkeley in 1938, spending additional years at the nearby Pacific School of Religion before being ordained by the Presbyterian Church. Rushdoony argued that the American Revolution had nothing to do with Enlightenment values of personal freedom, but was instead a conservative counterrevolution aimed at creating a Christian nation. Rushdoony wrote that Christianity and democracy are natural enemies, calling democracy "the great love of the failures and cowards of life." He argued for the application of Mosaic Law, prescribing the death penalty for civil crimes like bestiality, witchcraft, public blasphemy, homosexuality, adultery, and lying about one's virginity. He implied a denial of the Holocaust and supported both slavery and segregation, writing that the goal of civil rights groups "is not equality but power. The background of the Negro culture is African and magic and purposes of magic are control and power . . . voodoo songs underlie jazz, and the old voodoo, with its power goal, has been merely replaced with revolutionary voodoo, a modernized power drive." Rushdoony advocated for Christian control of American society through a theocracy. The concept is controversial, even among evangelists. But many on the Religious Right who seek church control of political institutions find in Rushdoony's writings something to support. Evangelical activists quote Rushdoony the way New Left radicals frequently quoted Karl Marx. |