|

| Journeying the Sixties: A Counterculture Tarot |

|

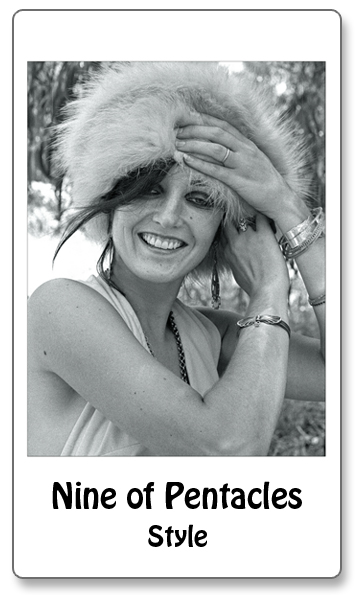

NINE OF PENTACLES "The fashion of the billionaires is finished, the society to which it belonged is dead. Equality today has one name: jeans, faded and torn. The word 'fashion; should be abolished from our vocabulary . . . Blue is beautiful this year, the next year it must be green. But who says so? Where is it written down? Why couldn;t people dress as they wanted to? Our fashion is founded on liberty . . . Comfortable, practical, free, personalized in the choice of accessories: that;s how I think people should dress." --Clothing designer Elio Fiorucci on the overthrow of high fashion, July, 1974 "We were dressing up to go have a grand time and to be looked at, but mostly to please ourselves. That was what was so exciting. No purpose, no ulterior motive to getting dressed except fun. It;s pleasurable to look strange or beautiful or medieval or American Indian." --Haight-Ashbury designer and purveyor of fashion Linda Gravenites, recalling the psychedelic style of the Sixties The Nine of Pentacles is what he or she wears, compiled from a stroke of luck that embellishes the psyche with accessories of beauty. It is the Tarot card of a very personal abundance presented here as a young woman in a garden, recreating herself with discarded clothes bought from a thrift store. It is the card of Sixties style. It is Venus in Virgo, an affectionate embrace of the versatile uses of old materials to create new looks and live new lives. The era;s cultural revolution in clothing atomized world fashion, previously the province of the insular but powerful creators of haute couture. As Arthur Marwick describes in his history of the Sixties, the period was marked by an unprecedented explicitness about sexuality, but also a new openness about the power of physical beauty. To satisfy a young and populous generation, clothes appeared that expressed its natural and youthful attributes: health, vitality, comfort, and sexual interest, as well as individuality and imagination. To dress up in the Sixties was in revolutionary ways to cover the body with erotic and assertive adornments. These might be very short skirts or faded jeans, see-through mesh blouses or t-shirts. They could be anything, bought anywhere or self-created from threads and fabrics. But more than clothing ever worn before, the fashions of the Sixties were, as Fiorucci said, founded on liberty. Post-World War II fashions, especially those created by Christian Dior that accentuated a woman;s breasts with pointy brassieres, offered a salute to an embryonic sensuality that was accentuated by the baby boom;s first teenagers. Short, tight skirts revealed the shape of a young girl;s buttocks while wide leather belts emphasized her narrow waist. Tight sweaters advertised a young woman;s emerging bust line. Boys took on a rebellious pose in t-shirts and jeans. Casual and sexy were the cornerstones of youth fashion as the 1960s opened on an era of youthful independence. And since teenagers paid as much as 50 percent of all money spent on clothes, their fickle tastes quickly gave the big fashion designers headaches. Glamour, for so long imposed by a reliable social conformity to fashion, was slowly giving way to the power of personal beauty and its distinctly tailored and idiosyncratic projection. By the mid-60s Western style had collapsed into an anarchical expression. High fashion took hold on London;s Carnaby Street beginning with Mary Quant;s revolutionary pop designs, including the at-once ubiquitous mini-skirt accessorized with the new seam-free pantyhose that made it possible. Women;s legs moved with a freedom not known since the Roaring 20s, while boldly displaying several inches of thigh. It was a powerful statement of comfort and sexuality that, combined with bright and varying colors, drew loud attention. It was also fashion only young women could comfortably wear and that firmly defined the line between their generation and that of their mothers. "The old could, if they wished, look like the young," wrote New York Times fashion journalist Maureen Cleave in 1967. "But the young must not on any account look like the old." Increasingly, clothing became an expressive art and an assertive form of beauty that men, too, found attractive. When the Beatles arrived on the scene with their Edwardian suits and moppish hairstyles, boys noticed how their softened sexuality aroused a female gaze. Men;s hair grew longer, reaching to the shoulders and beyond. Mustaches and beards might restore the textures of apparent masculinity, but long hair advertised a reacquaintance with the anima and a near androgynous sexuality. It was an appearance that other rock performers, notably Marc Bolan, Jim Morrison and David Bowie, projected with varying intensities and enormous success. Assertions of comfort and a liberated sexuality led women to stop wearing bras, and then panties, and then to discover the pleasure of wearing no clothing at all. Men might still arouse suspicions, but her sexuality was emerging as a woman;s dear and reliable friend, one she felt increasingly comfortable to be seen with. |