|

| Journeying the Sixties: A Counterculture Tarot |

|

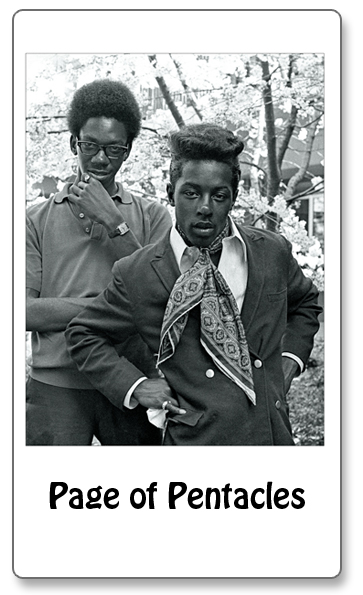

PAGE OF PENTACLES "We must create new models for adults who can teach their children not what to learn, but how to learn and not what they should be committed to, but the value of commitment." --Margaret Mead, "Culture and Commitment," 1970 "We are the people our parents warned us against." --Title of a 1968 book on the San Francisco Counterculture by journalist Nicholas von Hoffmann In 1966 two Berkeley High School students rehearse the imminent rupture of generational transition. One, his hair straightened, his clothes full of flash replete with a wild, suggestive scarf, presents an artifice of fashionable cool. He poses with a remarkable confidence worn on the sleeves of his dandyish adornments. Coming up from behind, however, is the new look of a friend who celebrates his hair's natural curl and has no use for flash. His confidence may not yet be apparent, but the change was coming. In June, Ebony magazine, a quality glossy widely circulated to millions of black readers, a magazine that traditionally ran advertisements for hair-straighteners and make-up to lighten dark skin, ran a cover story entitled, "The Natural Look: New Mode for Negro Women." As historian Arthur Marwick recalls, "The cover photograph was of a stunningly, beautiful black woman, an exquisitely proportioned and intensely appealing face, surmounted by close-cropped, fuzzy hair." Inside, the article was headlined: "The Natural Look: Many Negro Women Reject White Standards of Beauty." Within a year, Ebony ran another cover article on "Natural Hair-New Symbol of Race Pride" which for the first time used the Black Power slogan "Black is beautiful." The Afro hairstyle of black pride had surfaced finally to reach a mass audience and within months it was sported widely, a fashion statement that went much farther than fashion. It became a way to self-describe a new racial identity, not one imposed from without by words like "colored" and "Negro," but one drawn proudly from within and expressed in words like "black" and "African-American." Appropriately, the woman first pictured on an Ebony cover sporting her natural curl was not a professional model. Her name was Diana Smith and she was a 20-year old civil rights worker from Chicago. Other social transitions occurred quickly as larger gaps formed between the dominant culture and a youthful vanguard that seemed to oppose nearly all prevailing values. Sexual freedom, black power, anti-war politics, revolts on school campuses, a second feminist revolution, and the rejection of traditional religions burst into the open almost simultaneously. Why so many changes, and why so fast? And why all at once? Writing in 1969, City College of New York sociologist John Robert Howard weighed in with a scholarly theory of deviance that tried to explain the sudden and tenacious qualities of the new Counterculture. Howard distinguished between "vertical" deviance in which persons in a subordinate social rank "attempt to enjoy the privileges and prerogatives of those in a superior rank" and "lateral" social deviance in which persons in a subordinate rank "develop their own standards and norms apart from and opposed to those of persons in a superior rank." As an example of vertical deviance, Howard cited a 10-year-old boy who sneaks behind the fence to smoke a cigarette. The boy isn't in fundamental disagreement with the superior culture; he simply wants to enjoy its privileges before he's otherwise allowed. As an example of lateral deviance, Howard describes a teenager who smokes marijuana, thereby acting in a way opposed to the values of the dominant culture. Not all bohemians have been lateral deviants, but Howard notes that the Counterculture's antagonism toward authority did spread laterally through, first, the Beats of the 50s and, finally, down and laterally through young teenagers in the Sixties. "From the standpoint of the privileged, the situation becomes an extremely difficult one to handle," wrote Howard. As dissonance increases between the values of those in authority and those of a growing population of lateral deviants, authorities lose the capacity to induce conformity, explaining for Howard "the impotent, incoherent rage so often expressed by adults towards hippies . . ." The rapid growth of the Counterculture's laterally deviant lifestyle also helps to explain why so many of its members would wish to "drop out" of the dominant culture and form self-supporting communities together. Howard also pointed out that "if a society fails to seduce the lateral deviant away from this deviance it may move to cruder methods," including police harassment, repression, and even violence. |